Parvovirus is a highly contagious viral illness that usually affects young puppies. It is transmitted from one dog to another via the infected animal’s feces. The virus is shed in the feces typically for two weeks following infection. However, once the virus is within the environment, it can remain infective for months. It can infect any dog that enters a contaminated area and has not had proper vaccinations. Some dogs do not develop symptoms of parvovirus; instead, they are carriers of the disease, shedding infective feces for a year or more.

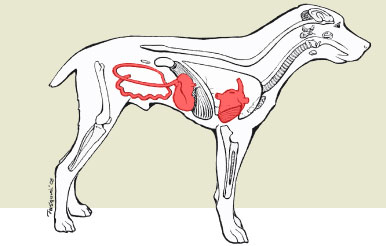

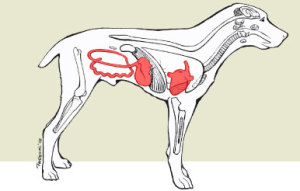

Parvovirus works by temporarily destroying the lining of the intestinal tract so that very little or no food or liquid can be absorbed. As a result, dogs that become infected with parvovirus may experience bloody diarrhea, severe vomiting, weight loss, and fever. In addition, because parvovirus also affects the immune system, limiting it from producing the white blood cells that protect against infection, dogs with the virus may develop other diseases.

Even when vaccines are administered properly and according to schedule, animals may become infected by parvovirus if they live within a contaminated environment. Because antibodies from the mother can inactivate the vaccine until the puppy is 16 to 18 weeks of age, preventing contact with infected animals or contaminated environments is critical. The use of dilute bleach (1:32) will kill the virus and is an effective cleaning agent. Always use cleaning products in well-ventilated areas. Keep all infected animals in strict isolation and prevent transmission of fecal material from one area to another.

It is rare for an adult dog more than two years of age to get sick from parvovirus. Rather, puppies are the most severely infected by the disease, and without appropriate medical attention, they may not survive the illness. However, there is a vaccine against parvovirus that should be given to puppies as a series early in their lives, and repeated every year thereafter. With appropriate medical attention, most of these dogs will survive, but the cost of treatment is much more expensive than the cost of proper vaccinations.

Often, diagnosis is suspected based on the history and physical exam findings. A complete blood count, which measures the number of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets, often will show an insufficient number of white blood cells. A parvovirus test, performed using a fecal sample, shows the presence of the shedding virus in the feces. Occasionally, a false negative result can occur if the virus has not yet begun to shed in the feces; thus, dogs that test negative often are re-tested if the veterinarian suspects parvovirus.

For puppies that receive medical attention and survive the first two or three days of treatment, the prognosis is good to excellent. Puppies between the ages of six to 18 weeks that do not receive treatment have a poor prognosis for survival. Older animals have a better prognosis than puppies and tend to require a briefer period of hospitalization. Ultimately, however, the prognosis is dependent on the individual animal’s immune system and the degree of illness.

The best prevention is proper sanitation of the environment and vaccination of young puppies. Vaccines should be given at six, nine, 12 and 16 weeks of age. Because they are more susceptible to parvovirus, certain breeds such as Doberman Pinschers, Rottweilers, Pit Bulls, English Springer Spaniels, and Labrador Retrievers may need additional vaccines as part of their “puppy series”. Please consult your veterinarian for any further information or recommendations.